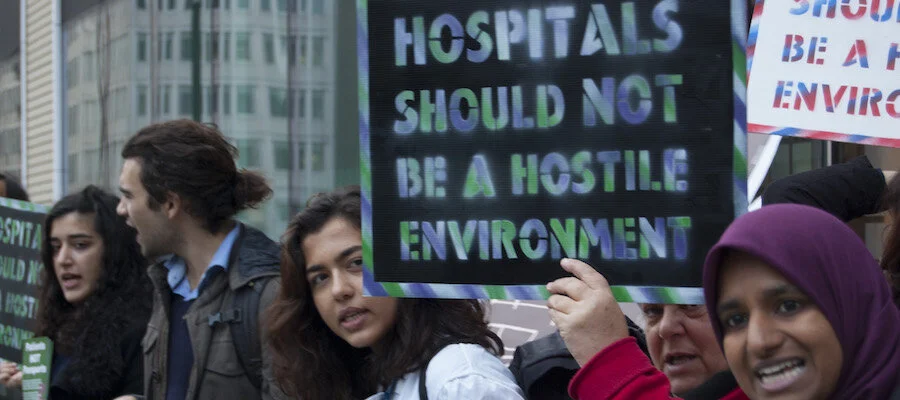

End the Hostile Environment

Patients not Passports have recently published a report about the international struggle for universal healthcare and ensuring access for migrants, and how we can learn from successful campaigns across Europe. The NHS New Deal will campaign to end The Hostile Environment. Read this piece by Daniel Button on how people have fought and won on migrants’ rights in other countries.

When the NHS came into being in 1948, chief among its founding principles was universalism. The principle of healthcare for all is as popular today as it ever was, commanding widespread support across the country. The problem, however, is that practice does not always follow from principle.

The Hostile Environment – which includes policies designed to limit access to the NHS based on migration status - means that many are deterred from seeking care, face greater delays in accessing treatment or have care denied outright. The NHS has begun to charge some people up to 150% of the cost of care upfront. Behind this, NHS Trusts share patient data to the Home Office, which is then used by immigration teams to track, detain and deport people.

Charging in this way risks introducing the notion that it is acceptable that some people should have to pay for their treatment or go without. Normalising the practice of charging patients for care, and introducing the bureaucracy to do so, opens up the possibility of charging for other groups of people. It could be part of a slippery slope away from universalism.

And it’s already having devastating consequences. In April, a Filipino migrant known as Elvis died at home with suspected coronavirus. He had lived and worked in the UK with his wife for more than 10 years, but was so scared by the hostility of Government policies that he did not seek any help from the NHS.

The government, who have been accused of basing policy on ‘anecdote, assumption and prejudice’, are unlikely to respond to evidence about the harm the hostile environment is causing in the health service. So what can be done?

A good start is to look at what’s happening internationally. Across a number of countries in Europe and beyond, there has been multifaceted resistance to similarly unjust policies restricting migrants rights to healthcare, with healthcare workers playing a leading role alongside local and regional governments, civil society, non-governmental organisations and migrant communities in demanding change.

When the Spanish government passed restrictions by Royal Decree in 2012, healthcare workers conscientiously objected to the policy and continued to treat migrants without charge, while regional governments chose not to implement the national policy, passing more inclusive policies locally. There were public demonstrations that spread across the country and over 300 civil society organisations signed up to publicly denounce the restrictions. This multifaceted resistance was instrumental in the government’s eventual decision to overturn the Royal Decree and expand migrants’ rights to healthcare. Similar successes have been achieved using similar tactics across the continent, from Italy to Sweden.

“networks of locally organised groups of healthcare workers are joining forces with migrants and NHS campaign groups”

In the UK, resistance is already gaining ground through the Patients Not Passports campaign, where networks of locally organised groups of healthcare workers are joining forces with migrants and NHS campaign groups. And there is precedent for this sort of action in the NHS’s own history. The government tried to introduce charges into the health system in the 1980s, eliciting widespread resistance from trade unions, migrant organisations and medical professionals under the banner of the No Pass Laws to Health campaign. Only seven months in the scheme was abandoned.

Campaigns from across Europe and the NHS’s own history demonstrate the potential that campaigns and organising can have on policies designed to undermine the principle of universalism that is held in such high esteem in the UK. To read more about what we can learn from international struggles for universal healthcare for all, check out our research here.